Textile Basics: Lecture #10 – Textile Finishing Processes (Part 1: Aesthetic Finishes)

Welcome back to our journey through the world of textiles! We’ve covered fibers, yarns, and various fabric construction methods like weaving, knitting, and non-wovens. But the story of a textile doesn’t end there. After a fabric is constructed, it undergoes a series of crucial treatments known as finishing processes.

Textile finishing refers to all the processes applied to a textile fabric after it has been manufactured (woven, knitted, or non-woven) to improve its appearance, hand (feel), and performance. Finishing transforms a “greige” (raw, unfinished) fabric into a product suitable for its final use.

Finishing processes can be broadly categorized into:

- Aesthetic Finishes: Modify the fabric’s appearance and hand.

- Functional/Performance Finishes: Enhance the fabric’s utility and performance properties.

Today, we’ll focus on Aesthetic Finishes, which are designed to make the fabric more visually appealing or to alter its feel.

1. Cleaning & Preparation Finishes (Often the First Step)

Before any specialized aesthetic or functional finishes can be applied, fabrics often undergo preparatory cleaning. These aren’t typically “aesthetic” in themselves, but they are crucial for allowing subsequent aesthetic finishes to work properly.

- Desizing: Removes sizing agents applied to warp yarns before weaving to improve their strength and reduce breakage.

- Scouring: A chemical washing process to remove natural impurities (like oils, waxes, dirt) from natural fibers, and processing oils from synthetics. This enhances absorbency and prepares the fabric for dyeing.

- Bleaching: Lightens or whitens natural fibers by removing natural color, preparing them for brighter or whiter finishes.

- Mercerization (for Cotton): A chemical treatment for cotton fabric or yarn that involves steeping it in a caustic soda solution under tension.

- Effects: Increases strength, luster, dye uptake (color vibrancy), and dimensional stability, and reduces shrinkage.

2. Enhancing Appearance & Hand

These finishes directly change how the fabric looks and feels.

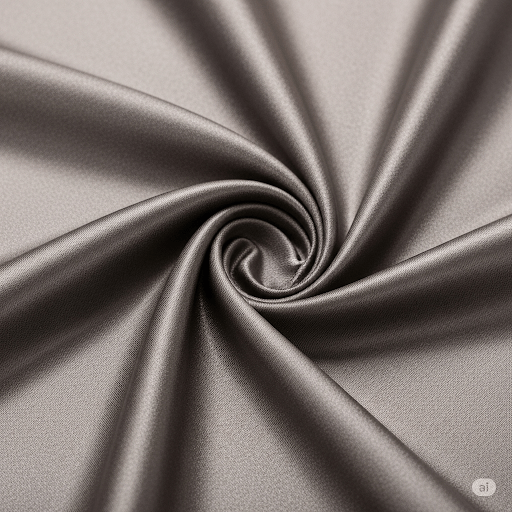

- Calendering: A mechanical process where fabric is passed through a series of heated rollers under pressure.

- Effects: Imparts a smooth, flat, and often lustrous surface. Think of ironing on a large scale.

- Variations:

- Simple Calendering: Basic smoothing.

- Glazing: Achieves a highly polished, semi-permanent sheen (often using resins).

- Cire: Produces a high-gloss, “wet look” or patent leather effect (using high heat and pressure, often on synthetics).

- Embossing: Creates a raised, three-dimensional pattern on the fabric surface (e.g., imitation brocade, moiré patterns).

- Sueding/Napping/Brushing/Sanding: Mechanical processes that create a soft, fuzzy surface by raising fiber ends.

- Sueding/Sanding: Uses abrasive rollers to create a very short, velvety nap, mimicking suede leather.

- Napping: Uses wire brushes or rollers with fine bristles to pull fiber ends from the fabric surface, creating a soft, fuzzy pile (e.g., flannel, fleece, velveteen).

- Brushing: A lighter version of napping, creating a soft surface.

- Shearing: A mechanical process that trims the surface fibers to create a uniform pile height, often used after napping or on pile fabrics like velvet or corduroy.

- Beetling (for Linen): A mechanical process where linen fabric is hammered to flatten yarns and create a lustrous, leathery surface.

- Plissé: A chemical finish (often caustic soda) applied in stripes or patterns to fabric (usually cotton). The chemical shrinks the treated areas, causing the untreated areas to pucker, creating a crinkled texture that doesn’t need ironing.

- Moiré: A calendering process that creates a wavy, watery, or wood-grain effect on ribbed fabrics (like faille or taffeta) by pressing two layers of fabric together.

- Stiffening/Weighting: Applying starches, resins, or other chemicals to add body, crispness, or weight to a fabric.

- Softening: Applying chemical softeners (e.g., silicone emulsions) to improve the fabric’s hand and drape, making it feel smoother or more luxurious.

Sustainability Considerations in Aesthetic Finishing:

Aesthetic finishing processes can have significant environmental impacts:

- Water Consumption: Many processes (especially mercerization, sueding, napping) are water-intensive.

- Energy Consumption: Heated rollers (calendering), drying ovens (sueding), and other machinery require substantial energy.

- Chemical Use: The application of resins, caustic soda, starches, and other chemicals, along with their subsequent disposal, can lead to water pollution if not properly managed.

- Air Emissions: Some chemical finishes can release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air.

The push for sustainable textiles encourages the development of finishes with lower environmental footprints, such as waterless dyeing, bio-based chemicals, and energy-efficient machinery.

In our next lecture, Lecture #11, we will continue our discussion on Textile Finishing Processes, but we’ll shift our focus to Functional/Performance Finishes, which add properties like water repellency, flame resistance, and wrinkle resistance.